Brittnay L. Proctor

Honey

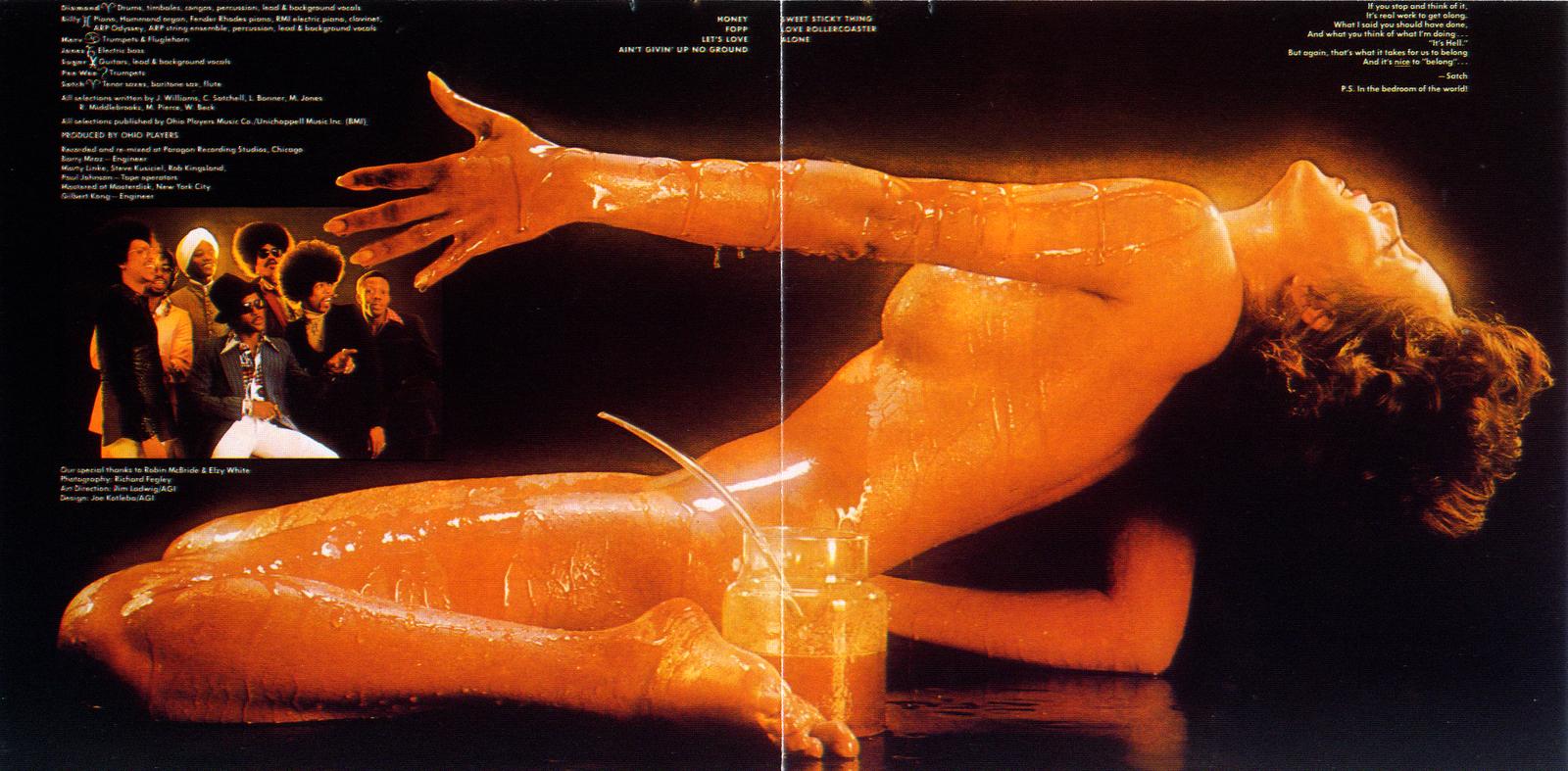

Full Inner Gatefold of the Album Honey, Ohio Players (1975)

Excerpt from work in progress (book manuscript on funk music and theories of black gender)

Between gatefolds and in the proverbial “cut” of black popular music LP’s of the 1970s, it is impossible to account for the labor of black femmes. Created out of glamour photos shot by former Playboy photographers, like Richard Fegley, the LP’s of black funk musician’s of the 1970s were contingent upon the spectacularization of black femininity. The rationale for this genre (a “type,” “kind”) of album art was to represent alluring and sexy forms of black femininity, while also representing a form of black masculine alterity rooted in a transgression against white libidinal economies that pose black masculinity as both monstrous and lascivious.

For example, using the visual economies of sperm (i.e. virility), the Ohio Players’ Honey (1975) features former Panamanian born Playboy playmate, Ester Cordet, covered in the sticky, mucilaginous consistency of warmed honey to mimic semen. The large exhibition of her body dramatizes black sexual praxis as the imago of black masculinity, while also erasing the labor conditions of the photo shoot for the album art: it is rumored that Cordet was burned by the honey at the photo shoot and developed erythema. (The horror surrounding) Her laboring body pairs with the title track of the album, “Honey.” “Honey” features the arresting crooning of Leroy “Sugarfoot” Bonner. Silky and viscous like the syrupy, ‘seed’-like honey that covers Cordet’s body, the love song is a tender and soft dedication to a lover, who is “sweet like honey.” The juxtaposition between Sugarfoot’s vocal performance on “Honey” and the album art totes the faux-line between masculinity and femininity, as also evidence by the band’s live performance of the song on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert on October 22, 1976 (Episode #4.13).

The example of the Ohio Players’ Honey (1975) is representative of a black masculine alterity that characterized most funk music of the 1970s. These performances of black masculinity embraced sex and the “funk” that accompanies laboring and they were wholly disinterested in anti-black formulations of black manhood as assimilable and non-threatening. Although rooted in a black masculine alterity, works like Honey (1975) also helped to sustain the nomological gender categories of “man” and “woman.” Instead of fully enveloping these forms of gender performance in re-representing black womanhood, many of these albums used the mimicry of the white ‘male’ gaze’s representation of (white) women’s bodies in a publication like Playboy, to represent black femininity. More troubling, the LP, in this context, erases the labor that births black masculinity. Performers like Ester Cordet are depersonalized. Or, terms like “sexual revolution” and “patriarchy” attempt to explain the composition of these works, sublimating the labor of black women/black femmes into the universe of white womanhood. Pointedly, these works reveal the totalizing force of labor on the (un)gendering of black subjects.

While the LP does not disrupt the episteme of captivity/mutilation versus liberated/bodily integrity that Hortense Spillers maps in her seminal essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” the LP, with its play with the nude form and toggle between transgressing and reproducing white masculine and feminine ideals, is a site of black gender theory. Black gender theory, by way of the LP, theorizes black people’s relationship to categories of gender as fraught, always contingent, and indeterminate. And while the LP, is a site of visual and sonic enclosure for captive subject positions (i.e. the black femme), it was and still is (with the new popularity of “vinyl”) a productive space for black artists to create discourse about topics like black gender constitution. Despite the confinement of blackness and black gender thinking via the format, the dimensions of the LP granted the space to engage black visuality, particularly the visual economies of black embodiment, with black sound.